E2 _ Life of the Townspeople_ Partitioned Row Houses (munewari nagaya)

- Commentary

- Nagaya is a residential structure composed of a building that is divided into several small units. Munewari nagaya referred to row houses that were formed by dividing the building into front and back units. The roof was made of thin shingles and the partitioned walls were thin. Since almost all of the materials used for the construction of these structures were either wood or paper, these wooden buildings were very susceptible to fires, and were therefore also called yakeya (burning houses). The most typical of these units were “kushaku niken no ura-nagaya,” which were 9-shaku (approx. 2.7 m.) wide and 2-ken (approx. 3.6 m.) deep, occupying an area of 3-tsubo (13.2 square meters) with a living room the size of 4.5 tatami mats. The nagaya that is reconstructed here consists of three such units and two units that are 2-ken wide and 2-ken deep with a 6-tatami size living room. Each unit features scenes of daily life inside the home.

E3 _ Publication and Information _ Bookstore of light fiction

- Commentary

- This model reproduces the facade of a bookstore selling light fiction and illustrations. It was modeled after “Kansendō,” the shop of Izumiya Ichibei, as depicted in the volume Tōkaidō meisho zue (“Famous Places on Tōkaidō,” 1797). Ichibei’s store stood close to the Tōkaidō, at Shiba Shinmei-mae Mishima-chō (present-day Shiba-Daimon 1-chōme, in Minato ward). This area was crowded with shops providing Edo-produced fiction and prints. It is not known when Ichibei opened his shop, but he began publishing illustrated satirical noveletters (kibyōshi) during the 1780s.

A few decades later he also issued many polychrome woodblock prints by Utagawa Toyokuni (1769-1825) and other artists. The shop of Izumiya Ichibei also sold scholarly books, maps, and text books.

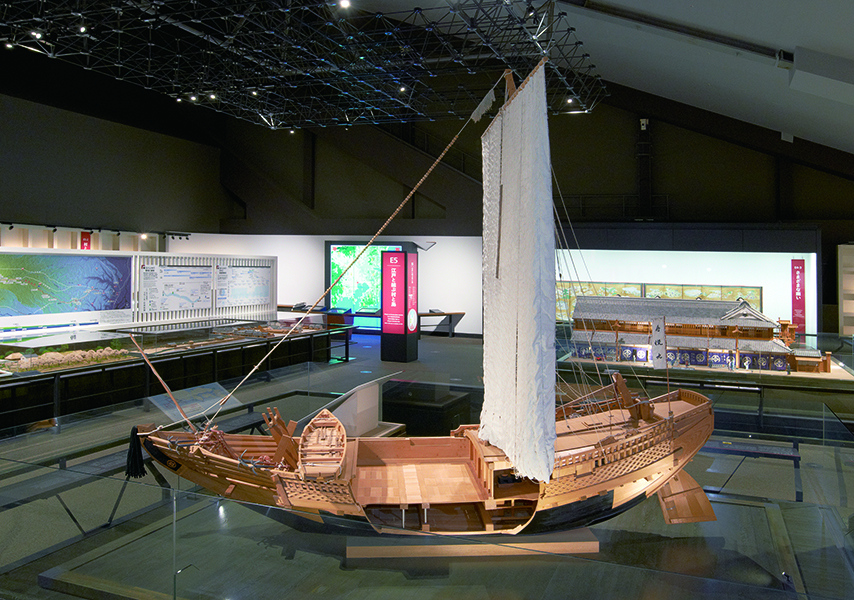

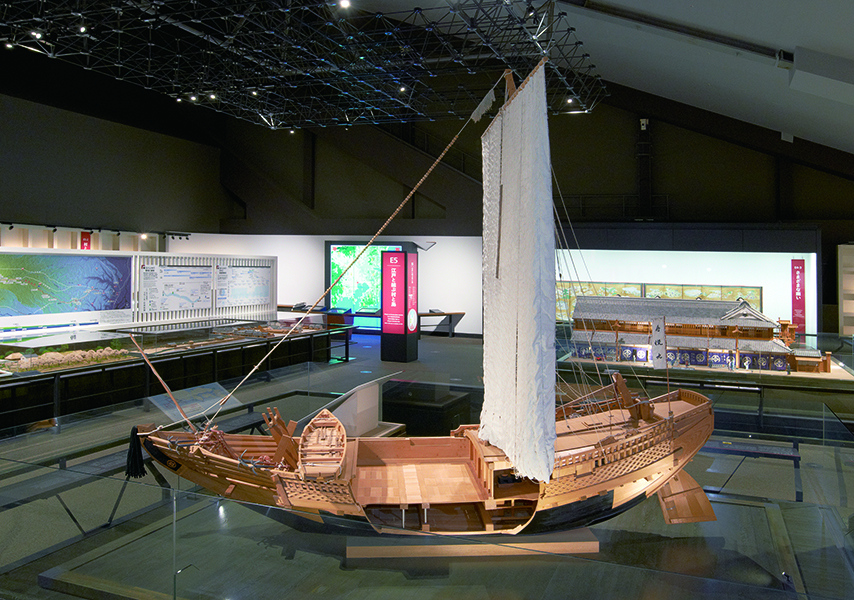

E4 _ Commerce of Edo _ Higaki Cargo Vessel

- Commentary

- Cargo vessels known as the Higaki cargo vessel (higaki-kaisen) sailed between Osaka, the “nation’s kitchen,” and large, consumer cities like Edo, carrying large quantities of daily necessities from the Kansai area, such as cotton, oil, and paper. The Higaki-kaisen was an essential means of transport along with the taru-kaisen (barrel vessels) that carried rice wine (sake) and other items. The name “Higaki” derives from the diamond-shaped lattice that adorned the sides of the ships. This replica is based on an illustration of a 1500-koku (about 270,000ℓ) Higaki vessel from the Bunka era (1804-18.)

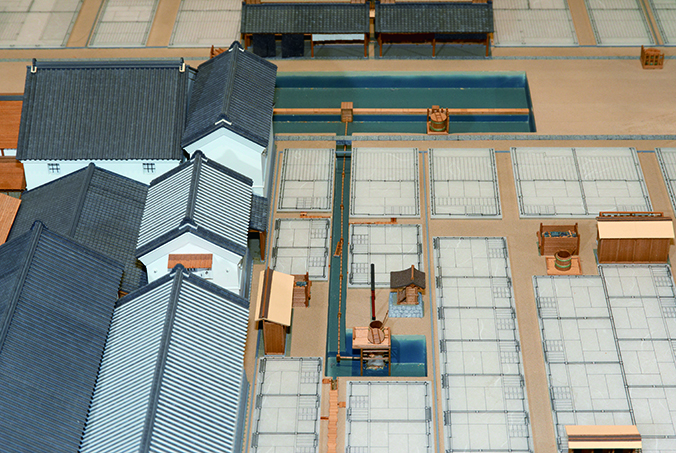

E4 _ Commerce of Edo _ Mitsui Echigoya Dry-Goods Store

- Commentary

- This is a recreation of the storefront of Mitsui Echigoya, a major dry-goods store of the Edo period that was located in Surugachō. The model is based on “Hon fushin e-zumen” [Construction Plan] (1832, Mitsui Bunko Library) and other sources. Mitsui Takatoshi, the founder of Echigoya, was born in Ise Matsusaka and in 1673, he established a dry-goods procurement store in Kyoto, then opened a sales store in Edo. The section that has been recreated here is the “Eastern Store” (higashi mise). In addition to this was the frontage section known as the “Main Store” (hon-mise) of about the same size. Thus, it is possible to get a sense of how big Mitsui Echigo-ya was.

E5 _ Villages and Islands Linked with Edo _ Tamagawa Waterworks and the Koganeibashi Bridge

- Commentary

- The Tamagawa waterworks was a water supply system that was built in response to the growing population of Edo. It is said that the waterworks between Hamura Village and Toranomon was built by Tamagawa Shōemon and Seiemon from 1653 to the following year. The distinguishing characteristic of the Tamagawa waterworks was its surveying techniques. The open ditches from Hamura to Yotsuya Ōkido covered a distance of approximately 43 kilometers with an elevation difference of about 100 meters. The fact that each 100 meters of flow would lower by about 20 centimeters speaks to the sophistication of the surveying technique.

E5 _ Villages and Islands Linked with Edo _ Water Guardhouse at Yotsuya Ōkido

- Commentary

- The Tamagawa waterworks took in water from the Tama river and a trench was dug approximately 43 kilometers to Yotsuya Ōkido. From there wooden stone troughs were used, and the water was taken underground (in subterranean drains), the water was then supplied to the southwest portion of Edo city and did not go into Edo castle or the Kanda waterworks. Water guard towers were placed on the junctions where water went from above ground open ditches into the subterranean drains, and these guard towers were facilities to manage the watertworks.

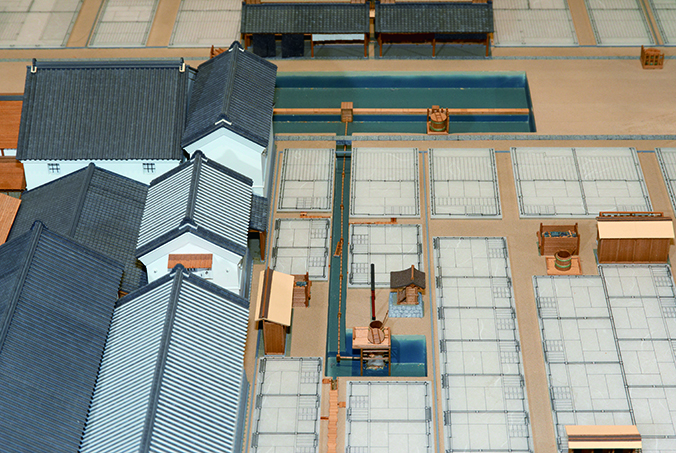

E5 _ Villages and Islands Linked with Edo _ Use of the Waterworks System

- Commentary

- This is a schematic model of the city in the late Edo period based on “Edo koken-zu” [Record of Edo Deeds of Sale] (Tokyo Metropolitan Archives) and “Amada-ke monjo” [Documents of the Amada Family] (Gunma Prefectural Archives). It is a typical machi, or township, with a street running through it and houses built on both sides of the street. The depth of each residential lot was 20 ken (approx. 40 meters), and the township consisted of merchant houses and nagaya row houses as well as wooden gates, gatekeeper’s hut, a guardhouse, and a fire lookout.

E6 _ Edo’s Four Seasons and Its Entertainment Districts _ Festival Float of the Kanda Myōjin Shrine

- Commentary

- This is a full-scale model of one of the floats (dashi) used in the Kanda Festival reconstructed based on existing floats in the Kantō area and illustrated materials. During the Edo period, Kanda Festival was held on the 15th day of the ninth month of each year. On this day portable shrines (mikoshi) accompanied by more than thirty festival floats and people in costumes paraded through the city, displaying the high spirits of the townspeople of Edo. Every other year, this parade was allowed into the precincts of the Edo castle to be viewed by the Shogun. This is a replica of a float that had been repaired in the late Edo period by the doll-maker Furukawa Chōen. It is the eighth float from Suda-chō, with the figure of Guan Yu, the Chinese military commander of Shu-han.

E6 _ Edo’s Four Seasons and Its Entertainment Districts _ Kanda Myōjin Festival Procession

- Commentary

- This recreation was made to show how the magnificent procession at the time was during the fabulous Kanda Festival. it was made by taking out representative festival floats and portable shrines from the pictures from that time. The festival floats are the chicken from Ōdenma-chō, the old man from Hatago-chō 1-chōme, and the Susanoo-no Mikoto from Sakuma-chō 1chōme. The portable shrine was Ninomiya. There were approximately 300 dolls arranged such as the gentlemen, float performers, carriers of the portable shrines and musicians.

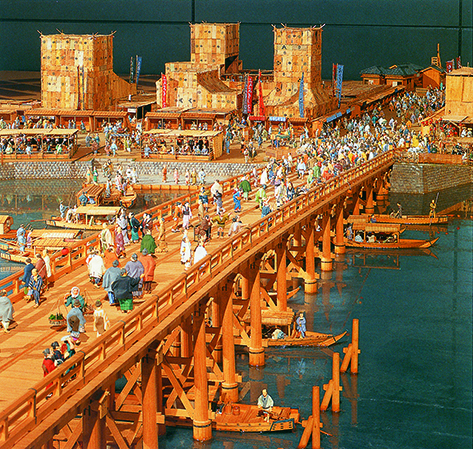

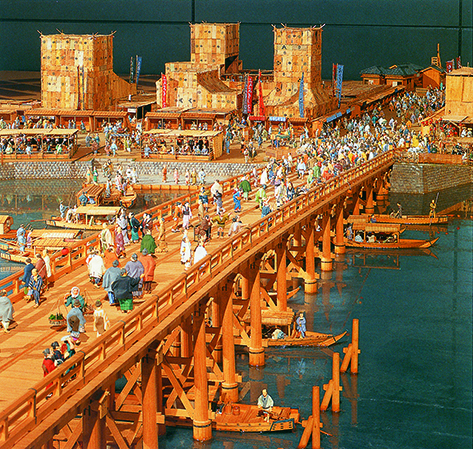

E6 _ Edo’s Four Seasons and Its Entertainment Districts _ Western Bank of the Ryōgokubashi Bridge

- Commentary

- The broad avenue on the west of the Ryōgokubashi Bridge was filled with teahouses, hairdressers, exhibition booths, and show tents offering acrobatics, kabuki theater, and much else. Here one could also find countless stalls serving sushi, tenpura, and broiled eel, vendors selling watermelons or morning glories, and a large variety of street performers. During the summertime, the season for fireworks, the river was crowded with all kinds of boats, large and small, open or with roofs. From these boats people watched the displays; other boats were used by vendors or those who launched fireworks.

This model, using some fifteen hundred figurines, portrays the “bustling spot” on the west side of the Ryōgokubashi Bridge during the 1830s. It is based on various law enforcement records issued during the Tenpō Reforms of the early 1840s.

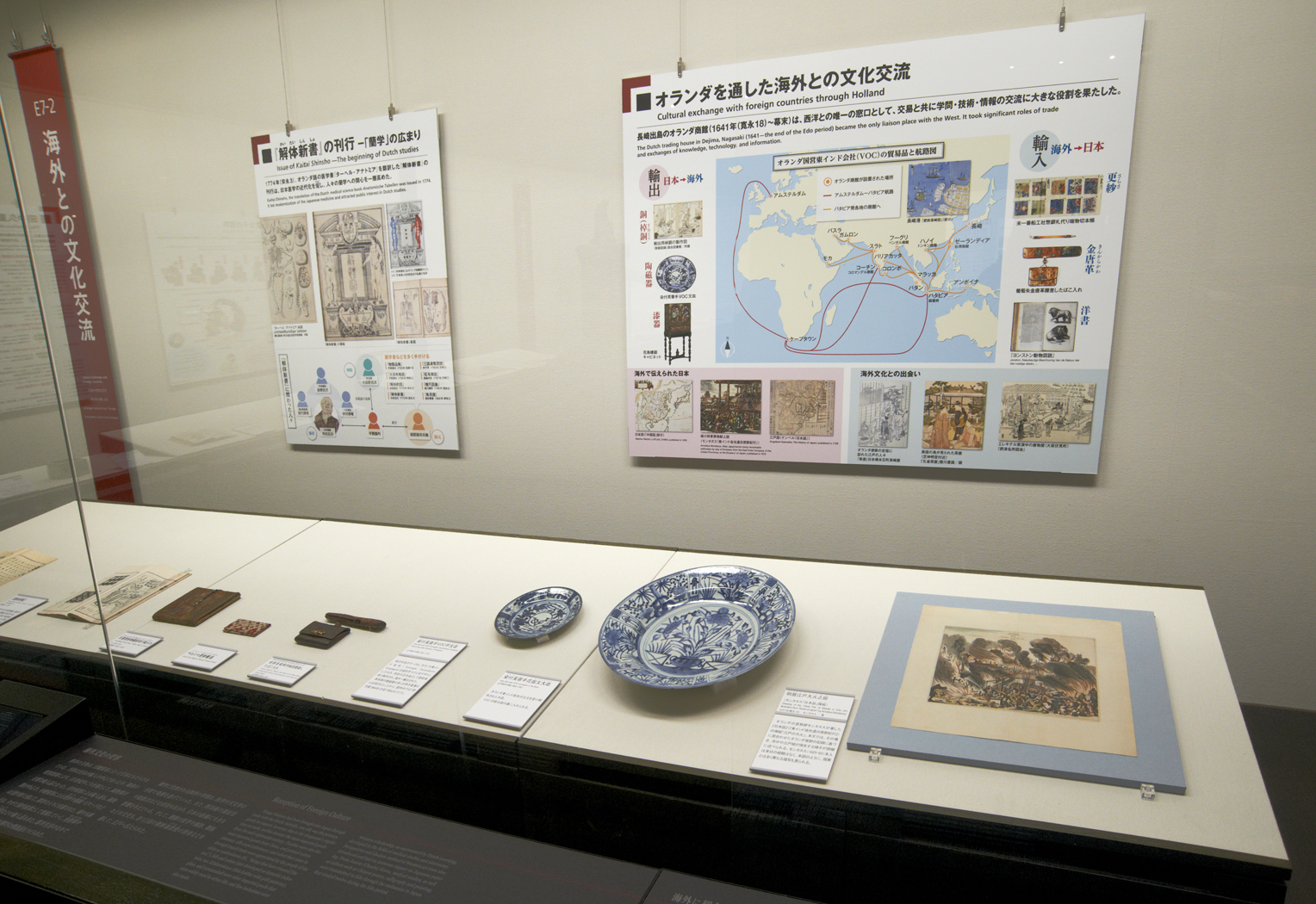

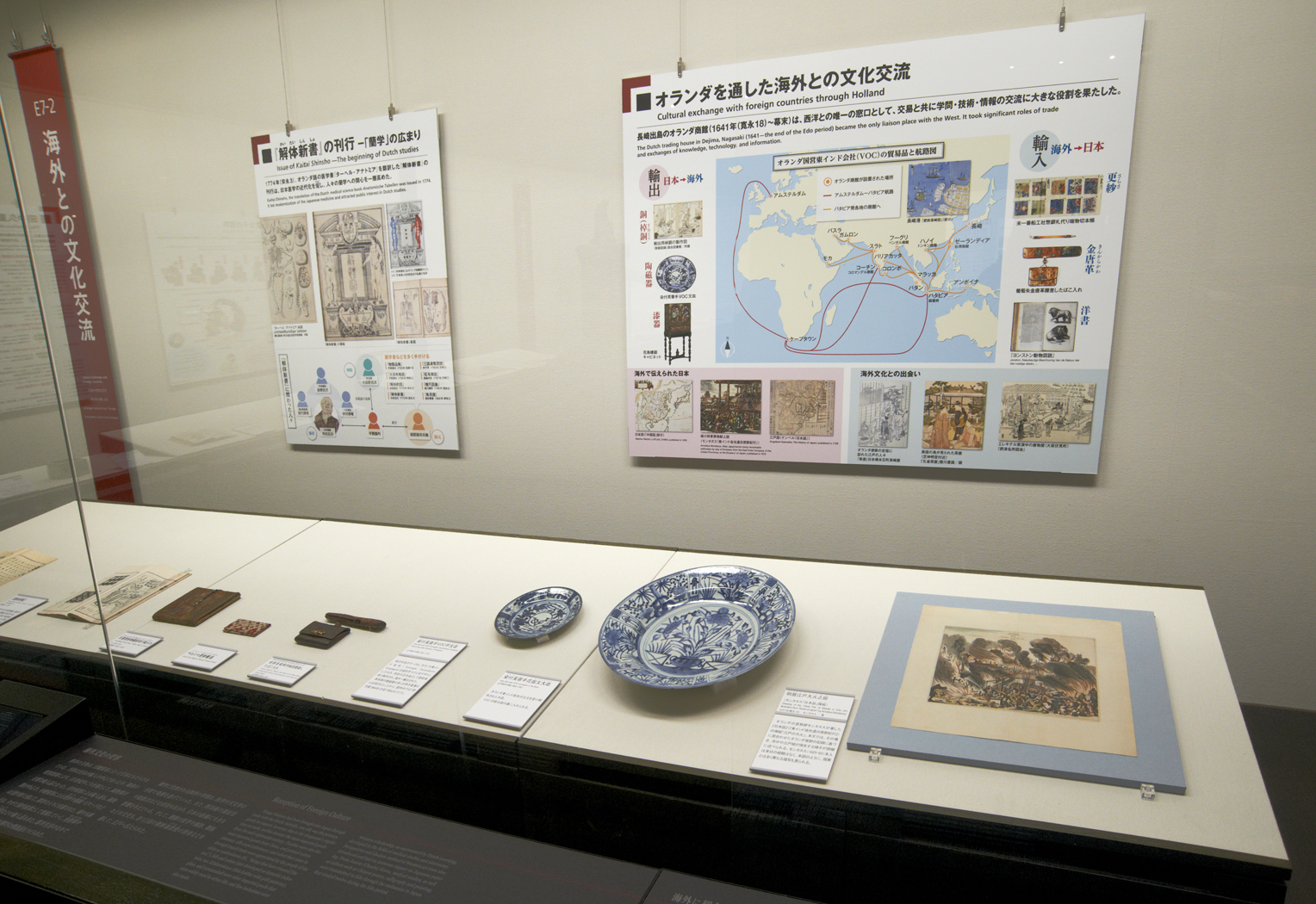

E7_ Cultural City Edo _ Cultural Exchange with Foreign Countries

- Commentary

- During the period of seclusion (sakoku), trade with foreign countries was limited to the one port in Nagasaki. Trade was controlled by the government in order to prevent loss of gold and silver. Nevertheless, imported goods brought by the Dutch and Chinese ships eventually permeated into the daily lives of the common people . In major cities like Edo and Osaka, there were occasional exhibitions of imported goods and shows of rare animals such as elephants and camels. Furthermore, the 8th shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune (1684-1751) eased the prohibition of importing Western books, and thereafter, rational and practical science of the West, as seen in the so-called "Dutch-Learning" school, was also introduced to Japan.

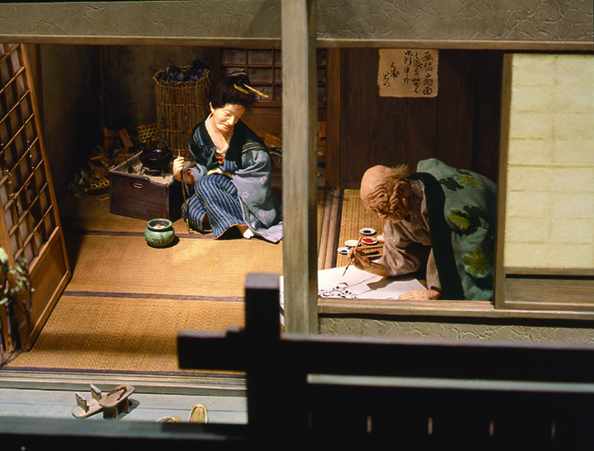

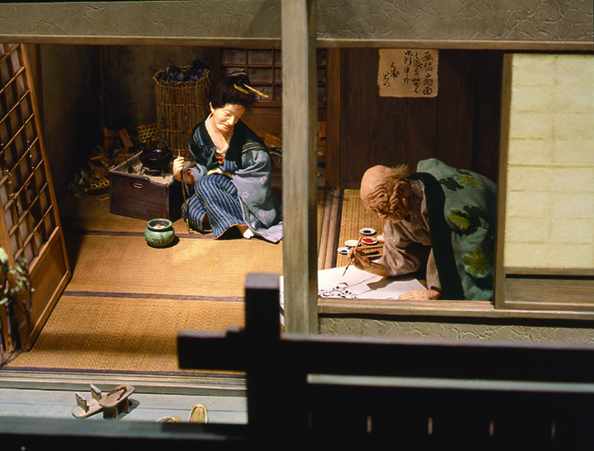

E8 _ Aesthetics of Edo _ Hokusai’s Studio

- Commentary

- This model is a replica of Katsushika Hokusai’s studio, based on the Hokusai karitakunozu [Illustration of Hokusai’s Temporary Abode] (National Diet Library), drawn by Hokusai’s pupil, Tsuyuki I’itsu. It is believed that Hokusai was born in Honjo Warigesui (present-day Kamezawa area in Sumida-ku, near the Edo-Tokyo Museum) and moved his residence more than ninety times during his lifetime. Here one can see Hokusai’s studio in one of his temporary rented abodes at Hannoki Baba (present-day 4-chōme Ryōgoku area in Sumida-ku). At this location the 83-year-old Hokusai lived with his daughter, O-ei. Hokusai’s masterpieces were produced in small, wretched houses like this one.

E9 _ Theatres and Pleasure Quarters _ Façade of the Nakamura-za Kabuki Theater

.jpg)

- Commentary

- Façade of the Nakamura-za Kabuki Theater, a prominent playhouse of the Edo period, is restored here at the full size with the width of 11 ken (about 20 meters) and a depth of 3 ken (about 5.5 meters). Common people and the nobility alike came here to forget the troubles of everyday life and free their minds in the world of Kabuki.This model is based “Nakamura-za omote no zu,” “Machikata kakiage” and Edo meisho zu-e. Signboard was created based on the kaomise performance of the eleventh month of 1805 (“Seiwa Genji nidai no yumitori”). (Picture billboards were illustrated by Torii Kiyomitsu XI).

The picture billboard for “Shibaraku” was specially added as it is a symbol of Edo Kabuki.

E9 _ Theatres and Pleasure Quarters _ Structure of the Nakamura-za Kabuki Theater

- Commentary

- Nakamura-za is one of the representative kabuki theaters from the Edo period. The theaters in Edo were frequently rebuilt or remodeled because of fires, but this model was an attempt at reconstructing the structure of the theater based on the "Machikata Kakiage" (Records of Town Officials) records from 1809 that were about the Nakamura-za in Sakai-cō (present-day 3-chōme Nihonbashi Ningyō-chō area in Chūō-ku). In this time period, the gable-like structure of the stage known as the hafu had already disappeared, but it was temporarily constructed depending on the play.

E9 _ Theatres and Pleasure Quarters _ Sukeroku on Stage

- Commentary

- Here is an imagined scene from Sukeroku one of the representative Kabuki plays from the Edo period. Sukeroku was first performed in 1713 by Ichikawa Danjūrō II, and it subsequently became part of the group of works known as “Soga tales” that depict the vengeance of the Soga brothers Jūrō and Gorō. It was completed with the title “Sukeroku Yukari no Edo Zakura.” The story develops around the whereabouts of Tomokirimaru, a treasured sword of the Minamoto Clan, with the protagonist Sukeroku, his lover Agemaki, and Ikyū who has an illicit love for Agemaki as main characters.

This model has recreated and displays the same props and costumes that are used on the stage today.

E9 _ Theatres and Pleasure Quarters _ Special Effects Behind the Scenes of Kabuki Theaters

- Commentary

- By the late Edo period, a variety of special effects were used in kabuki plays. Especially popular was Tōkaidō Yotsuya kaidan (“Ghost story of Yotsuya on the Tōkai Highway”) written by Tsuruya Nanboku IV (1755-1829), in which unique devices were used to allow the ghost to move about freely on the stage. Devices that produced such special effects were manipulated by the backstage staff that paid close attention to the movements of the actors on the stage. For the purpose of the display, lighting has been changed; mirrors are placed in back to allow viewing of the mechanism of the devices used to create these special effects.

E10 _ From Edo to Tokyo

- Commentary

- This section links the Edo Zone and the Tokyo Zone. It focuses on Katsu Kaishū, who was born in Honjyo Kamezawa-chō (present-day Sumida-ku), very close to the Edo Tokyo Museum, and explores the major historical turning point, when Edo became th modern national capital Tokyo.

T1 _ Tokyo in the Age of “Civilization and Enlightenment” _ Chōya Shinbun Newspaper Company

- Commentary

- Tokyo’s modern journalism opened with the founding of Tokyo Nichi-Nichi Shinbun (“Tokyo Daily News”) in 1872. This was followed by the publication of more newspapers in rapid succession. Chōya Shinbun (“Chōya Newspaper”) was founded in 1874. It attracted much attention because the newspaper’s president Narushima Ryūhoku (1837-84) and editor-in-chief Suehiro Tetchō (1847-96) severely criticized the Meiji government, gaining popularity along the way.

T1 _ Tokyo in the Age of “Civilization and Enlightenment” _ First National Bank (partial reproduction)

- Commentary

- With the introduction of modern banking system, the First National Bank was established in Kabuto-chō with the main objective of financing the “promotion of industry.” The stock exchange and insurance companies were concentrated in Kabuto-chō, which was conveniently located near Nihonbashi. This area would eventually become Japan’s foremost financial district. The building is in the “gi-yōfū” (lit. “quasi-Western-style) style—its structure was built using the traditional Edo-period method, while the exterior adopted the Western architectural design. Shimizu Kisuke II, who designed and constructed the building, had studied the structure of Western architecture as he took part in the construction of Western-style buildings at the foreign settlement in Yokohama. He was the pioneer of modern architecture and worked on Western-style buildings such as the Tsukiji Hotel and the Mitsui House in Suruga-chō.

T1 _ Tokyo in the Age of “Civilization and Enlightenment” _ Ginza “Bricktown”

- Commentary

- After a devastating fire of February 1872 that burned the area between Ginza and Tsukiji, the new Meiji government planned and built the Ginza “Bricktown” as a model city for the modern nation-state.

The plan focused on the Ginza area, which linked Shinbashi station to the Tsukiji foreign settlement and various government offices. Fireproof houses (made of brick) were constructed, and roads were widened and improved. The city was designed by the British architect Thomas James Waters (1842—1892) and the Ministry of Finance took charge of the construction. A year after the fire, the Western-style district had revealed itself.

T1 _ Tokyo in the Age of “Civilization and Enlightenment” _ Rokumeikan

- Commentary

- Rokumeikan, designed by the British architect Josiah Conder (1852-1920), was constructed in November 1883 in present-day Hibiya and became a symbol of Westernization. More than one hundred dolls are installed in this model to represent the exuberant social life at the time. The model offers a full view of the second floor ballroom, in which one could see people dancing at a ball.

T1 _ Tokyo in the Age of “Civilization and Enlightenment” _ Nikorai-dō

- Commentary

- “Nikorai-dō”, which is hidden among tall buildings today, is located on a hill in Kanda Surugadai, and was once visible from throughout Tokyo. The official name of this edifice is the Holy Resurrection Cathedral in Tokyo, but the people of Tokyo call it “Nikorai-dō,” named after St. Nicholas (1838-1912), a missionary who devoted himself to improving Japanese-Russian relations during the Meiji period. The original dome and the bell tower were destroyed during the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. The existing dome and other parts of the building were designed by Okada Shin’ichirō and reconstructed several years later.

T2 _ Behind the Scenes of “Enlightenment”

- Commentary

- While the wave of "civilization and enlightenment" swept through the city, much of the lives of the common people remained unchanged from the Edo times. The school system, for example, was not immediately modernized, and many private schools had its roots in the old terakoya (temple schools).

T3 _ Tokyo and the Industrial Revolution

- Commentary

- In the capital Tokyo, industries developed extensively through the policies of fukoku kyōhei (lit., "rich country, strong military") and shokusan kōgyō (lit., " more production through new industry "). The "domestic Exhibition for Encouragement of industry" held in Ueno allowed the meeting of domestic and international technology, and contributed to the development of local industries. Middle to late Meiji saw a rapid expansion of heavy industries; at the same time, various problems such as factry noise and poor working conditions arose.

This section introduces these various aspects of industrial development in Tokyo.

T4_ Urban Culture and Recreation _ Ryōunkaku (“Asakusa Twelve-Stories”)

- Commentary

- Ryōunkaku, a tower also known as the “Asakusa Twelve-Stories,” was designed by the British engineer William K. Burton and completed in 1890. It functioned as a symbol of Asakusa and appeared on many souvenir pictures. This tower was highly popular until it collapsed in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923.

Ryōunkaku was approximately sixty meters in height. It was an octagonal structure made of brick up to the tenth floor, and the eleventh and twelfth floors were made of wood. The eleventh and the twelfth floors were equipped with telescopes for peering into and over the city. Ryōunkaku boasted Japan’s first elevator, leading to the eighth floor. For safety reasons, however, the operation of the elevator was eventually halted.

T4 _ Urban Culture and Recreation _ The Façade of Denkikan Movie Theater

- Commentary

- When moving pictures first came to japan, they were shown at theaters for plays and tents that toured around; however, the Denkikan (electric hall) on the sixth block of Asakusa became japan’s first permanent movie theater in 1903. There was no sound in the moving picture at that time, so it was necessary to have a commentator. The person who had bee the voice of the exhibitions up to that point Somei Saburō took over as the commentator, and he added to the theaters popularity.

T4 _ Urban Culture and Recreation _ The Movie Theater District in Rokku

- Commentary

- Around 1908 the motion pictures became quite popular, and the small exhibitions on the sixth block changed into movie theaters one by one. This model is a three-dimensional recreation of the sixth block that was Asakusa in January of 1912 when it was in the process of taking shape as a movie theater district. This was recreated referencing the structural diagrams patched together from the "requests for the construction of a new building in the Asakusa Park" (in the Tokyo Metropolitan Archives) that were needed for every new structure. The ornaments like the signboards and flags were created based on pictures in the archives.

T5 _ The Great Kanto Earthquake _ “The Great Kanto Earthquake: Conditions of Fire within the City of Tokyo” (Animation)

- Commentary

- The video that shows the changing situation of fire that swept through the city of Tokyo during the Great Kanto Earthquake. This animation is based on “Tōkyō-shi kasai dōtai chizu Taishō jūninen kugatsu” (Monbushō Shinsai Yobō Chōsakai, 1924) and used as reference “Taishō jūninen kugatsu Tokyo kasai dōtai ryakuzu” in Nakamura Seiji, Senkyūhyaku nijū sannen kugatsu Tōkyō ni okeru daijishin ni yoru daikasai (1925); Inoue Kazuyuki, Teito daikasai-shi in Shinsai Yobō Chōsakai, Shinsai Yobō Chōsakai hōkoku dai 100-gō (1925); “Reppū ni aoraretaru kasei” in Keishichō Shōbōbu, Teito Daishinka kiroku (1924), etc.

T6 _ Modern Tokyo _ Map of the Thirty-Five Wards of Greater Tokyo: Railway Routes and Changing Population

- Commentary

- This map schematically shows the areas and population of Tokyo from Taisho to early Showa eras and the railways that were extended throughout the city. As the button is pressed, the map will show the changes in population in the 35 wards between 1912 and 1935 in seven stages and colors, and the national and private railway routes will also light up accordingly as the lines were opened. No stops are indicated for all private streetcars other than the Keiō Electric Streetcar.

T6 _ Modern Tokyo _ Housing in the Downtown Shitamachi Area

- Commentary

- This is a house modeled after a four-unit row house in Tsukishima, Chūō ward ( built in the late Taisho era < early 1920s> ), where many factory workers lived. The model restores a typical lifestyle of commoners during the early Showa era ( mid-1920s to 30s ).

Many such houses had no electric lighting in the toilet and kitchen. When lighting was needed in the kitchen, an electric lamp was pulled over from the adjoining two-tatami room. In those days, before gas and water services were widely available, kitchens were normally built facing the alley, so that water could be fetched and fire built outside. Gas was not provided to such row houses until the 1930s; plumbing in each apartment was not common until after World War II.

T6 _ Modern Tokyo _ Japanese-Western Style House

.jpg)

- Commentary

- This is a partial restoration of a house that was built in the beginning of the Taisho era (-1912-1926) in Higashigotanda, Shinagawa. The house was renovated in 1937 according to the design of Ōkuma Yoshihide, and was dismantled and restored for museum exhibit. The dining/living room is built in a mountain cottage style, which had been popular during the Taisho and early Showa eras. Sliding doors and curtains are used between this room and the adjacent Japanese-style room to retain the ambiance of each room. The lighting and furniture were also designed by Ōkuma to match the room.

T7 _ Air Raids and the Citizens of Tokyo _ A Wartime House

- Commentary

- Until air raids became increasingly common, many residents of the Tokyo downtown areas lived in rooms such as the one reconstructed here. To prevent window glass from shattering during bombing raids, windowpanes were taped. A special lampshade was used to prevent light from leaking outside. Steel helmets and other safety gear were kept close by. A radio set was used to obtain information about air raids. As food shortage became more serious, rice that was nearly unpolished began to be rationed. Such rice was polished by placing it in a bottle and beating it with a stick.

T7 _ Air Raids and the Citizens of Tokyo _ Balloon Bomb (reconstructed model)

- Commentary

- The balloon bomb was developed by the Japanese Army to attack the American mainland, and it was a weapon with a bomb or fire bomb that was hung from a flying balloon. This balloon was 10 meters in diameter that was made by sticking Japanese paper together with konnyaku paste. This model was created based on the reports in the National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C. that currently has custody of an actual bomb balloon. The balloon’s diameter is approximately 1/5 its real size and the gondola portion is approximately 1/2 of the real size.

T8 _ Tokyo Revived _Shinjuku: The Black Market at Night

- Commentary

- In the beginning of September in 1945, an advertisement for Shinjuku Market with the slogan, “Light Shines from Shinjuku,” was published in the newspapers. Black markets were formed immediately after the war in areas in front of train stations that had become burnt fields after the air raids. These markets sold items for daily use, such as pots and knives, bowls, and geta clogs. This model, “Shinjuku: The Black Market at Night” is based on photographs and oral surveys, with some added detail based on speculations.

T9 _ Tokyo during the Times of Rapid Economic Development _ Hibarigaoka Housing Complex

- Commentary

- The Hibarigaoka Housing Complex was built in -1959, in the area spanning across three towns in Kitatama-gun: Tanashi and Hoya (present-day Nishi-Tokyo), and Kurume (present-day Higashi Kurume). All 2,714 units were rental, and occupancy began in April of 1959. There were several types of units, ranging from 1 DK (1 room with a dining/kitchen) to 4 DK (4 rooms and a dining/kitchen), but the most common type was the 2 DK (2 rooms and a dining/kitchen) unit. Each unit was equipped with an entrance door with cylinder lock and a bathroom. Considering that most apartment houses at the time had shared bathrooms, or even shared toilets and kitchens, these facilities ensured residents’ privacy and led to the establishment of a new concept of mai hōmu (lit. “my-home,” or the trend toward owning one’s own home).

T10 _ Tokyo Today

- Commentary

- This section will explore the lifestyle and culture of the period that is still new to our memory. It divides the period between the 1960s to 2000s into five sections, comparing the changes Tokyo underwent in each decade. we will look at how Tokyo was transformed and phenomena that attracted people’s attention.

Stratigraphic sample of the ground below Edo/Tokyo

- Commentary

- Remains of Edo have been discovered in many places in central Tokyo. This model reproduces ground strata below Hitosubashi High School (at Higashi Kanda, in Chiyoda ward). Until the medieval period, this location was the Hibiya inlet, filled with reeds. It was reclaimed in the early Edo period and became part of a temple ground. The temple burned down during the “Meireki Fire ”of 1657, and row houses were built here. These remained in place until after the endo of the Edo period. More recently, the area was visited by two disasters: the great Kantō earthquake of 1923 and the Tokyo air raids.

In the four meters of strata contained this model one can read the history of Edo/Tokyo.

Museum Laboratory

- Commentary

- The Museum Laboratory, located at the end of the gallery, is a space where you can "Feel and experience." The Laboratory is divided into two sections: The first is a model of a house from the 1950s. Visitors may take their shoes off and enter the sitting room to experience the life before electric appliances and Western lifestyle became common.

The other is a space for special programs, where visitors may try using various tools from the past or participate in workshops associated with themes of feature exhibitions.

“See with Your Hands” Exhibit

- Commentary

- The “See with Your Hands” Exhibit displays objects that can be felt and appreciated by visually impaired visitors. It is located on the fifth floor, next to the information desk. Miniature versions of life-size models in the main exhibition gallery, such as the “Nihonbashi Bridge,” “Façade of the Nakamura-za Kabuki Theater,” and “Float of the Kanda Myōjin Shrine,” are displayed with captions in braille. Also on exhibit are Ōkubi-e (lit. “large-head pictures”; close-up Ukiyo-e portraits of Kabuki actors, etc.) by Kitagawa Utamaro and Tōshūsai Sharaku that have been recreated in three-dimensional relief-work to feel the outline of the picture, as well as the realistic touch of the hairdo. The exhibit offers a new approach for all visitors, visually impaired or not, to enjoy the museum.

.jpg)

.jpg)